On day jobs and daydreaming

By martha

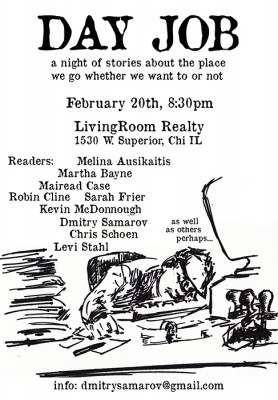

This is a (lightly) revised version of a piece presented February 20, 2014, as part of Day Job, a night of stories about work (and, it turned out, play) organized by artist Dmitry Samarov, in conjunction with his exhibit at LivingRoom Realty.

When people ask me what I do, I often joke that I have five day jobs. I have so many day jobs, I complain, that I don’t have time for the night jobs – the creative, life-affirming, desperately unmonetizable work that all this paid labor is supposed to be supporting. But that’s life in the new economy, right? The problem is, I’ve never been very good at playing the field. I was in a serious, long-term relationship with my career for years, and when we broke up a few years ago I spiraled out into promiscuity, looking for love in every gig I met. I had a hard time keeping it casual and then, when those short-term freelance jobs couldn’t give me what I wanted – every goddamn time — I would slide, once again, into despair.

So, a few weeks ago I went on a quick trip to New York with one of my regular day jobs. We’ve actually been together for a few years now and this one, at least, has settled into a comfortable routine, even if there’s still a bit of awkward tension. I try to stay poised and pretty when we’re together. We’re not watching bad TV in our sweatpants just yet, me and this job.

Because, this job, you see, is kind of a brainiac – what it is, really, is an academic journal of opera studies. The journal is held in high esteem by a very small number of musicologists, dramaturgs, performance studies people, and other miscellaneous academics, and has pretty much no relevance, or readership, outside this rarefied circle. And, while I’m not an academic, and I don’t know much about opera — or I didn’t when I started — it’s my charge to keep things on track; to keep the overcommitted, easily distracted thinkers whose thoughts fuel the journal from wandering off and getting lost in the thickets of dissertation defenses and departmental politics. This, basically, takes about ten hours a week, give or take, out of my life. It’s not bad, really, when all is said and done.

Every once in a while, though, it stands up and demands a little more commitment – and thus, I wound up in New York in early February for our board meeting and a conference on Prince Igor, a 19th-century opera by the Russian composer Aleksandar Borodin that was premiering in a new staging that weekend at the Met.

Now, Prince Igor is the tale of a man who makes very bad choices. A man blinded by hubris who, in the very first scene of the opera, defies the blazingly bad omen of a full solar eclipse and leads his men into battle with the Asian warlord to the east. The army is, of course, destroyed, Igor is taken prisoner by the enemy, his homeland is reduced to rubble, the women are raped, his wife is distraught, etc., etc.

It’s also four hours long, and by the time I made it to the conference early the next morning, I was weary. A familiar cloud of doubt descended as I made the rounds of the conference room. What am I doing here? Who is this job? It doesn’t really care about me – the real me, underneath this carefully de-linted sweater. It only cares what I can do for it.

As the assembled scholars dug into the previous night’s production my mind wandered. Musicologists debated the unstable narrative tropes of the medieval epic and the contemporary challenges of Orientalism in 19th-century opera. I wondered whether my paycheck had gone through in time to cover the rent. You should be trying harder to meet the right job, my inner monologue scolded. A nice job, with prospects, and good intentions for the future. This here? This is getting you nowhere.

By the time we broke for lunch I was considering sneaking out early. No one would notice; I didn’t even really need to be there. But instead I just went and got a bagel. And while I was sitting in an upper west side diner, licking the last of the whitefish salad from my fingers and checking my phone, I discovered that I had been dumped. One of my other jobs – a job that had sought me out and courted me, had made me feel so special that despite the various red flags it was throwing up I had let myself get excited about our future. And now? Now it turned out this job was seeing some other writer, and she was so excited about their new relationship that it was all over Twitter.

I walked back to the conference, blinking back hot embarrassing tears. Surely everyone on 86th Street could see that I was unlovable, unworthy of even the basic courtesy of a text message saying, “I’m sorry, I’ve met someone else.”

I settled into the back of the room simmering in a stew of self-pity and humiliation. My face burned; my mind buzzed. Around me the dialogue continued: musicologists and dramaturgs and performance studies people — some well-known thinkers at the peak of their careers; others junior scholars scrambling their way onto the tenure track, but all of their academic reputations carefully built on moments such as this, moments that entailed the informed consideration of questions of operatic scope.

Heroism! Hubris! Love! Failure! Redemption!

At the end of Prince Igor, the humbled hero turns his back on the life of sensual delights offered by his benevolent captors (long story) and returns to his devastated city-state, where he vows to redeem himself, rebuild and start anew. Based on a historical event from the 12th century, it’s a national epic on par with the Niebelungenleid and Beowulf, and while the score pales in the face of the Ring Cycle, it, you know, holds its own as allegory.

And somehow, as the afternoon rolled on, the fact pierced my private pouting that here in this room my day job – my boring, sort of nerdy day job — was publicly investigating the eternal tension between duty and pleasure; between men and women; East and West; body and mind. And though this was happening in an environment so hermetically sealed that a very involved discussion of the theatrical deployment of a stage full of poppies as a visual metaphor for the escape into oblivion failed to include a single reference to the death of Philip Seymour Hoffman, whose funeral was that day taking place 40 blocks south – I was soothed.

My mind calmed; my humiliation at my other job’s heartless betrayal was replaced first by anger – what an asshole! – and then acceptance. Because that other job? It was pretty high maintenance. It made big promises, but had trouble returning my emails. Frankly, I was better off without it.

I sat in the back of the conference room and as the conversation unspooled, my left brain kept tabs on the proceedings at hand as the right drifted into daydreams. I remembered lost loves and mistakes made in the face of phenomenally bad omens. And I didn’t panic. It’s all going to be OK. There are other, better jobs in the world; jobs that will treat me right, and I lost myself in visions of a future spilling over with love and loss, success and failure. I am lucky, I realized in that hot conference room and that uncomfortable chair. Lucky that my day job isn’t afraid to talk about its feelings, to engage with big emotions. I’m lucky to have this job to remind me that the day to day grind can still unfurl at operatic scale. I know there’s no future for me and this day job – but that doesn’t mean it can’t still surprise me – deliver comfort even, and occasionally joy.